Editors Note: This article was published on News Growl by Steve Goodale on February 5, 2019. News Growl has subsequently removed their website and given the Libertarian Party of Georgia permission to republish the article here as it does a great job expressing Georgia ballot access laws.

Georgia ballot access laws, long considered by experts to be the most restrictive in the nation, are now under attack on two fronts.

A 2017 lawsuit, backed up by two Supreme Court decisions, is currently working its way through the courts and may eventually force changes to the system.

A quicker route would be reform through legislation. A proposal with multipartisan support has been drawn up for this year’s legislative session and may soon appear before the state’s Governmental Affairs Committee.

America’s foremost authority on ballot access legislation, Richard Winger, ranks Georgia’s laws as “the toughest in the nation.”

Any reform, whether through the courts or the state legislature, would be seen as a huge victory for ballot access activists across the country.

Denying Georgia voters a choice 60% of the time

During the recent Georgia gubernatorial election, Georgia’s difficult history with voting rights – allowing eligible voters the opportunity to cast a ballot – became an issue of national prominence.

The state’s equally troubled history with ballot access – the process of getting a candidate’s name on the ballot – received practically no attention at all.

Ballot access reform activists argue that deciding who gets to appear on a ballot is just as important as deciding who gets to cast a ballot.

The problems in Georgia are real, not just theoretical: Georgia’s 1940s-era laws are so restrictive that over 60% of Georgia’s state legislators ran unopposed in the 2018 midterm general election.

“Georgia ballot access laws are some of the harshest in the country,” says Winger, who besides being a leading authority on the issue is the editor of Ballot Access News. “Stopping people from voting is not the only way to undermine a democracy. Denying equal access to the ballot is just as toxic.”

Georgia is especially under fire for its two-tier system, which prevent independents and minor parties from building experience in lower-level partisan races.

Qualifying for the ballot for statewide races in Georgia is difficult (the Libertarian Party is currently the only group other than the two major parties with statewide race ballot access), but qualifying for any other office, including the State House, State Senate, or US House, is practically impossible. No third party candidate has successfully petitioned to appear on a Georgia ballot for a regularly scheduled US House race since the rules were tightened in 1943.

The lack of competition is exacerbated by the regular failure of the two major parties to compete against each other. In the 2018 midterm elections 110 out of Georgia’s 180 state representatives ran unopposed in the general election. 33 of 56 state senate races were also only contested by one party.

Besides the lack of competitive races, stifling competition at lower-levels also blocks independent candidates and insurgent parties from gaining experience with elective office the way politicians in other parties do.

“Independents need to start at the local level,” said Luanne Taylor, who unsuccessfully tried to get ballot access for a Georgia House race in 2018. “It’s foolish to try to elect an independent to the White House when independents can’t even get on the ballot at at the state level.”

Taylor believes there is a public perception that less restrictive ballot access laws will lead to too many spoiler candidates running. She says this explanation defies the reality of the choice given to most Georgia voters.

“You need three candidates for a spoiler effect,” she explained. “Georgia is lucky to have two.”

What makes Georgia ballot access laws so awful?

Getting your name on the ballot in Georgia is relatively straightforward if you self-identify as a Republican or Democrat. People who self-identify as an independent or with a third party face huge obstacles.

“To appear on the ballot for US House I would need to collect signatures from 5% of the ‘active voter’ population between January and June of any election year,” explained Libertarian Party of Georgia vice-chair Ryan Graham. “That equates to roughly 20,000 signatures, but because the term ‘active voter’ is a slippery concept in Georgia you really need 40,000 signatures to prevent being disqualified.

“Collection rates vary wildly depending on the district,” continued Graham. “But even at 5 signatures an hour (which would be a good rate in many places) you’d need 8,000 man hours to get someone on the ballot for US House in Georgia. That’s the equivalent of eight people collecting signatures full time for six months without a break. No independent or third party candidate has those sorts of resources.

“It would be different if everybody had to do this, but Republicans and Democrats are exempt. While we are out sweating in the summer heat, asking voters for an intrusive amount of personal details, our opponents are out campaigning and raising money. Even if we do somehow get on the ballot, they have a six month head start.”

Keeping Georgia safe from communism

Georgia ballot access laws were tightened after the Communist Party attempted to register their candidate for president on the ballot in 1940. At the time, appearing on the Georgia ballot was simply filling out a form. The Communist Party placed its presidential candidates on the Georgia ballot in 1928, 1932, and 1936 with no problem.

Georgia ballot access laws were tightened after the Communist Party attempted to register their candidate for president on the ballot in 1940. At the time, appearing on the Georgia ballot was simply filling out a form. The Communist Party placed its presidential candidates on the Georgia ballot in 1928, 1932, and 1936 with no problem.

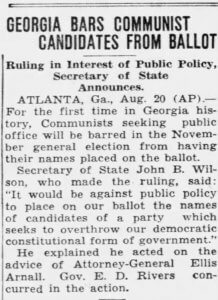

Despite having no legal authority to do so, Georgia Secretary of State John Wilson decided to turn down the 1940 Communist Party application. “It would be against public policy to place on our ballot the names of candidates of a party which seeks to overthrow our democratic constitutional form of government,” he explained to the Associated Press.

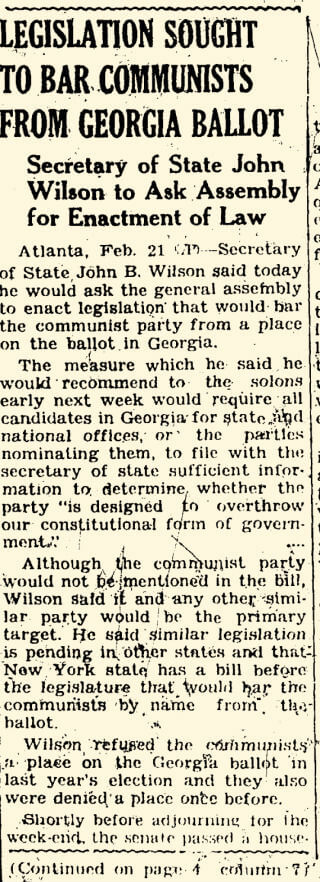

The Communists only had a tiny presence in Georgia in the 1940s and lacked any real party infrastructure whatsoever. Wilson wanted a permanent, legal solution to prevent them from accessing the ballot in future anyway. With his encouragement the 5% petitioning law was passed in 1943. The plan worked – Communists never troubled Georgia voters again.

The highly restrictive legislation did more than simply keep Georgia safe from Communism, however. It also kept Georgia legislators safe from competition – for decades.

The highly restrictive legislation did more than simply keep Georgia safe from Communism, however. It also kept Georgia legislators safe from competition – for decades.

“Since the 1943 legislation no third party candidate for US House has ever qualified, and no independent for US House has qualified since 1964,” Richard Winger told News Growl in an email.

The lone independent who bucked the trend in 1964 could not succeed today, Winger explained. “Back in 1964, the petition wasn’t due until October, the signatures weren’t checked, they didn’t need to be notarized, and no counties were split up among different US House districts. Petitioning was much easier in Georgia back in 1964.”

Over time the rules for statewide candidates have been gradually relaxed. To gain statewide ballot access currently requires signatures from 1% of all Georgia active voters – still no mean feat. The Libertarian Party has maintained statewide ballot access since the 1990s.

But the rules for downballot races have not been reformed, and in many ways have only grown more restrictive over time. Currently an independent or third party US House candidate must pay their filing fees in March – months before they find out if their petitioning will be successful. The $5,220 is not refundable for candidates who fail to qualify.

Georgia ballot access laws under legal pressure

In November 2017, four members of the Libertarian Party of Georgia hoping to gain ballot access for a US House race filed suit against then Secretary of State Brian Kemp.

Citing their First Amendment right to freedom of association, and Fourteenth Amendment rights to due process and equal protection, the plaintiffs argue that Georgia ballot access laws are unconstitutional.

Bolstering the case are two Supreme Court rulings that have struck down similar two-tier ballot access laws in Illinois.

In a 1979 case, Illinois State Board of Elections v. Socialist Workers Party, the court struck down rules which required more signatures to run for mayor of Chicago than for statewide office.

A decision delivered by Justice Thurgood Marshall stated: “[E]ven when pursuing a legitimate interest, a State may not choose means that unnecessarily restrict constitutionally protected liberty… and States must adopt the least drastic means to achieve their ends. This requirement is particularly important where restrictions on access to the ballot are involved.”

Illinois legislation was tested again in the Supreme Court in 1990 with Norman v. Reed. With only Justice Antonin Scalia dissenting, the court again confirmed that Illinois could not require more signatures for local races than statewide races.

Speaking to News Growl, Libertarian Party attorney Bryan Sells confirmed that the Georgia case is still ongoing and that he feels optimistic that, given enough time, the case will succeed.

Litigation is a slow process, however.

Multipartisan support for new legislation

The quickest route for reform of Georgia ballot access laws would be through new legislation.

Democratic State Representative Dar’shun Kendrick has recently sponsored a bill which would vastly improve ballot access for all Georgians, regardless of party affiliation.

Clearly seeing the issue as part of the state’s wider democratic reforms, Kendrick told News Growl, “I believe it’s good for our democracy in general to allow as many options for voters on the ballot.

“Access to the ballot shouldn’t be a partisan issue but an issue of sustained and better democracy,” she continued.

“I hope some colleagues will join me, particularly given this past election and the fresh look I think others will take at voting in general.”

Since Kendrick spoke to News Growl, Republican State Rep David Stover has agreed to cosponsor the bill. A second Republican is believed to be considering cosponsorship as well. If all goes to plan the bill could soon appear before the House Governmental Affairs Committee.

Besides support from major party legislators, the proposed reforms are also supported by the Libertarian Party of Georgia, Unite Atlanta (the local affiliate of Unite America), independent candidate Luanne Taylor, and the Georgia Green Party.

Unite Atlanta leader Amanda Swafford argues the proposed changes would actually help Democrats and Republicans. The current restrictions encourage people who do not genuinely support either major party to run on their tickets anyway.

“With much less restrictive ballot access,” she explained. “Third party, unaffiliated candidates and others seeking political office are not forced into party primaries in Georgia where the requirements for ballot access are exceptionally easier.”

If successfully passed, the new rules would eliminate stricter petitioning rules for local races, and lower the number of required signatures for all races (not just statewide races) to 1% of active voters or 200 active voters – whichever number is lower.

With renewed general focus on democratic reforms, and the pressure of a court ruling possibly forcing the state’s hand in future, Georgia ballot access activists are feeling their most optimistic in decades. Still, even getting ballot access restrictions acknowledged as an issue by legislators can be a struggle.

At January’s 57th annual Wild Hog Supper in Atlanta, an event widely attended by Georgia political insiders, Libertarian Party of Georgia chairman Ted Metz tried talking up the proposed law but struggled with the issue’s low profile.

“It was discouraging to have to explain the petitioning requirements to so many of the legislators. They have no understanding of the process for third party and independent candidates to get on the ballot,” he said.

“One representative, who made sure to let me know that she was a Democrat, insisted that Libertarians already had ballot access. After explaining that Libertarians only had ballot access for State-wide seats and non-partisan races, and that all other positions required petition signatures from 5% of the registered voters in the prior election, she said, ‘So, you can run for School Board, that’s non-partisan.’”

Not only politicians are to blame

Georgia’s history of noncompetitive races is a longstanding issue (the Republican Party failed to field candidates for Governor for decades until the 1966 election). The problem is so pervasive, and so infrequently discussed, it is hard to argue that the blame lies only with reluctant legislators.

Richard Winger believes the wider political establishment, including political journalists, are at fault.

“The big newspapers in Georgia simply don’t talk about this,” he told News Growl. “We have tried many times to get an editorial or at least an op-ed in the Atlanta paper, but they won’t do it.”

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution was accused by Libertarians of anti third-party bias its coverage of the 2018 gubernatorial race. When it was revealed that Ted Metz had been invited to the second televised debate, the AJC Political Insider Jolt column called it “disappointing news.”

AJC political reporter Greg Bluestein also tweeted disparagingly about third party candidates in November saying, “Count your blessings: we could be headed to a January runoff in these two US House races if there was a third-party candidate.”

For a previous article, AJC journalist Jim Galloway told News Growl that calling Ted Metz’s inclusion in the debate “disappointing” was meant only to reflect the opinion of readers who did not like having Metz in the debates. He did not provide further comment for this article.

While the Georgia media is ambivalent at best about a more competitive political system, activists are still hopeful they will come round to their point of view over time.

“The support of the media to make the system in Georgia fairer would be extremely helpful,” said Libertarian Ryan Graham. “Hopefully the fantastic work being done by Representative Kendrick will be noticed by everyone and given appropriate coverage. Someday, hopefully before too long, Georgia will no longer have the worst ballot access laws in the country.”